Where Are The Indian Working Women?

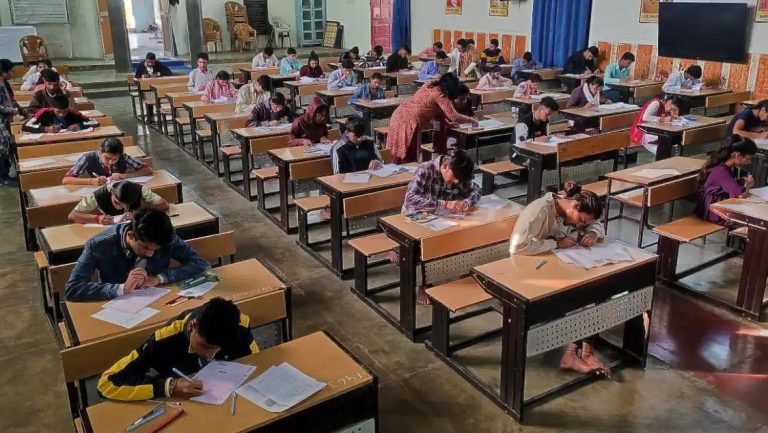

Indian women have been attending schools and universities like never before, and female education levels in the country are a success story.

Yet the percentage of women in the workforce has gone down over time.

Data from the International Labour Organization (ILO) states that the employability gender gap in India is 50.9%, with only 19.2% of women in the labour force compared to 70.1% of men.

Another report from World Bank figures from 2021 shows that fewer than one in five Indian women are formally employed, although most work in India is in the informal sector-agricultural or domestic work-which often doesn’t get counted.

The question is why do people educate their daughters if their labour participation is so low?

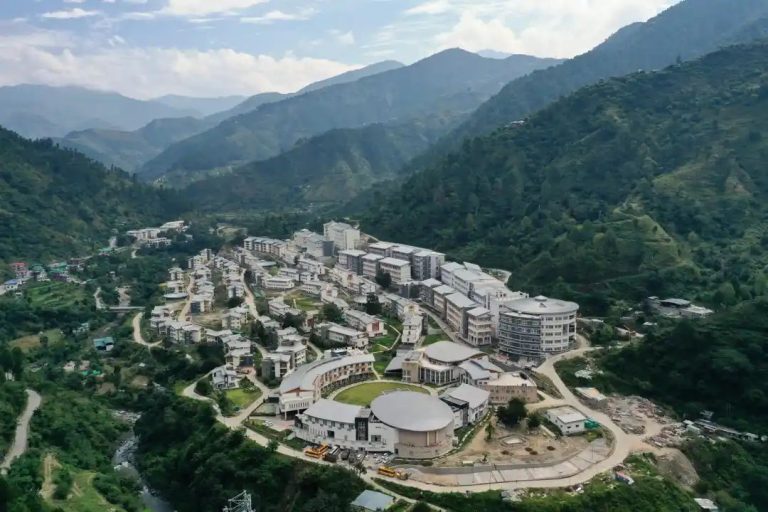

Rakhi Chaturvedi, an Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Guwahati professor, who was also a part of one of the most important household surveys in India in 2022, believes she now has an explanation.

As she documented the surveys, she believes that the rising education levels for women are largely driven by higher marriage prospects and not by job prospects.

“Nowadays, most families of sons are looking for educated daughters-in-law, not so they can contribute to family income but so they can produce highly educated children,” says Chaturvedi.

While Chaturvedi reasons this decline as the creation of educated housewives, Deesksha Kakkar, a category leader of Beauty and Hair Care at P&G India, believes that more mentorship is needed.

“In one of our campaigns, we have talked to hundreds of female STEM dropouts in India to understand why this happens. We have found out that 21% of them are not working, while 62% of them are in arts-related jobs. From the same survey, she found that 81% of them cite a lack of role models and mentors as the main reason for dropping out of STEM, so it is no surprise that these women are still driven to take on careers even after dropping out,” says Kakkar.

In hindsight, Kakkar says that there are numerous female-and even male-mentors available, but access to them is limited. “Mentorship is important for creating a pipeline for strong female leaders, but without support and role models, women in STEM fall through,” she adds.

Gita Kumari, who lives in Assam and works as a housekeeper, said she believes her three daughters need a bachelor’s degree to find suitable husbands.

In their dimly lit home on the outskirts of Guwahati, Kumari, a 40-year-old who never attended school, beams with pride because two of her daughters have been married to a well-reputed family.

“Having an educated woman at home is now a status symbol,” said Chaturvedi.

Some academics say it is rooted in not just household norms but also external problems: a lack of jobs, employer bias, and gender-segregated work among others.

“Educational progress was externally driven. The government made it a priority,” said Neerja Birla, founder and chairperson of Aditya Birla Education Trust. “When external constraints are eased, you see results,” she highlighted.

“While the data shows that the only area where we are seeing change is education, I believe that educational progress among women has done little to change the family,” says Birla, adding that today’s Indian women are more literate and educated than ever before. They’re enrolling in schools and colleges in greater numbers and staying in school longer than previous generations did.

As household incomes rise, women are dropping out of India’s workforce simply because they can afford to. Many no longer have to do back-breaking tasks in agriculture or other manual labour.

“As the economy grows, women retreat from work, in part because women’s work is seen as a standby or emergency measure,” says Tasneem Khan, a sociologist and a member of Akshara Centre, an NGO for women and children in Mumbai. “The moment the family becomes economically stable, they expect the woman to get out of the labour force.”

“So women move in and out of employment, depending on their family’s needs,” says Khan.

That’s the case for many lower-income families too. Gajraj Sharma, an auto-rickshaw driver in Mumbai, says it was only when inflation spiked this autumn that he and his wife discussed the possibility of her working outside the home.

“With food prices going up, we’re struggling to pay the children’s school fees,” Sharma explains. “There’s no way we can survive on a single income right now,” he added.

Pune: The FPJ Highlights Stories Of Woman Coolie, Driver, Bus Conductor, Police Officer On International Women’s Day

‘Women should not work outside the home’

Despite their country’s fast development, lots of Indians still have conservative ideas about a woman’s role in the family.

“Family is the priority for many women across the world, but especially in a country like India that’s very traditional. We still live in joint (multi-generational) families with obligations and a glorified image of women as mothers sacrificing, caring, and nurturing,” says Sakshi Chitre, a housewife living in Mulund. “The other aspects of a woman-as a competitor or achiever with aspirations-are not given much importance,” she said.

“As a married woman, when you’re staying in a (joint) family, you are not able to keep everybody happy,” Chitre recalls adding that her mother-in-law wasn’t supportive.

Even after that, Chitre, who was travelling with her daughter on a Mumbai local train, says she wants her daughter to pursue Chartered Accountancy,

When asked about what she thinks about the lower female labour participation rate, Chitre says if the statistics show India’s female labour rate at around 20%, it doesn’t mean 80% of women aren’t working.

“Women do a lot of unpaid work-running a household or planting and harvesting on a family farm-that doesn’t get counted. Often, it’s because workers, including women themselves, might not realise these types of labour should even be considered as such.