How Strong Leaders Morph Into Tyrants: Assessing the Cost of Exit and Heightened Ruthlessness

Usually, when a leader reaches this ruthless phase it becomes politically incorrect to say that they may have once been reasonable, or at least more reasonable, with some genuine intention to provide good leadership to their country.

I am not suggesting that the initial good intention is always the case. The main result in this paper is to show that no matter where an authoritarian leader starts from there will be a tendency to deteriorate over time. However, I believe that to deny that there may be good intentions at the start, as though evil intention is an axiomatic truth, hurts an objective analysis of dictators and totalitarian regimes and thereby thwarts the development of policies and strategy to block such unwanted turns of events as we have seen repeatedly through history.

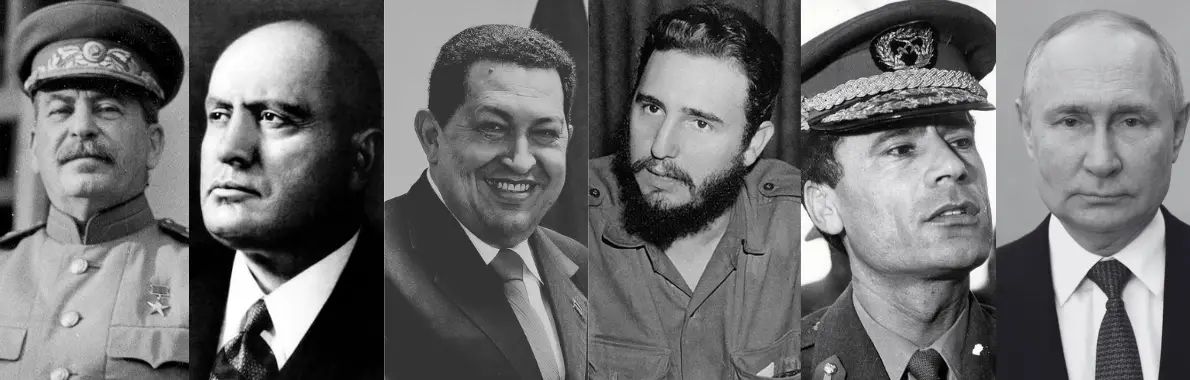

Examples jump out at us: Joseph Stalin, Benito Mussolini, Hugo Chavez, Fidel Castro, Kim II-sung, Robert Mugabe, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, Muammar Gaddafi, Daniel Ortega. In case these examples seem inadequate, after I began working on this paper, Putin invaded Ukraine, giving us a reminder that he had been left out. So let me add: and Vladimir Putin.

The paper uses simple, plausible assumptions and provides, by a step-by-step analysis, a surprisingly clear explanation of this propensity of leaders in power for long to morph into someone tyrannical and evil. What the paper tries to explain is the puzzle summed up by Stephen Kinzer (2021): ‘For most of his life [Daniel Ortega] was in passionate rebellion against [Somoza’s dictatorship and] everything it represented. Then, in what seemed an astonishing about-face, he began replicating it. With precision and design, he has created an insular, dynastic tyranny that eerily resembles the one against which he fought decades ago.’

For strong political leaders who stay in power for a long time, there are many changes that occur in their environment that can be cause for concern. We know that the information and news that such leaders get become increasingly biased. Their staff and minions, concerned not to upset the leader, give their boss the information the boss would like to hear. It is likely that Mao Zedong did not learn for a long time that his Great Leap Forward had failed and was causing one of the great famines in world history, instead. It is likely that what Putin believes is happening in Ukraine is far from what is happening in Ukraine. His reputation for tyranny and brutality must ensure that his staff will give him the news he wants to hear.

Further, the psychology of tyrants is often very different from ordinary mortals. Some of them are probably unaware of their own brutality or under the belief that it is done in the best interest of the nation. It is impossible to know if they actually believe in this or create these delusions to be able to live with themselves.

The aim of this paper is to focus on a slender cut of this reality and draw attention to a natural result. No matter what the initial intention of a leader seeking power, it is easy to take steps to prolong their tenure, which one step at a time may seem natural, but in their totality traps the leader in political evil and oppression that they cannot escape.

The most poignant statement of this tragic human predicament occurs in Shakespeare’s Macbeth (Act III, Scene IV), when Macbeth tells his wife:

‘I am in blood

Stepp’d in so far that, should I wade no more,

Returning were as tedious as go o’er.’

If the leaders are innately evil, their ending up practicing evil, would not be a surprising result. By focusing on the case of leaders with good intention and then showing how they end up as tyrants, this paper explains why this transformation of leaders who remain long in power is so ubiquitous. It should be emphasized that the model is not about where the leaders start—good or bad, but about the process by which they deteriorate, wherever they start.

Dictator’s choice

Though the paper is an exercise in theory, it owes its origin to a personal experience.

In September 2013, I met Daniel Ortega in Managua. The meeting had nothing to do with the World Bank mission that had taken me to Nicaragua. As a student in India and, later, England, I had heard and admired the achievement of Ortega in overthrowing Somoza’s corrupt regime. It was a long meeting where we talked about the Sandinista revolution and the challenges faced by Nicaragua. Given the sordid accounts that have subsequently emerged of Ortega’s oppressive and tyrannical behavior (Kinzer, 2021), I regret the decision to meet him.

I was also left with a troubling question: How could this happen? How could Daniel Ortega, who struggled, suffered and eventually overthrew the corrupt tyrant, Anastasio Somoza Debayle, morph into a creature similar to the one he overthrew? Was it a case of one freak individual and his psychology, or is there something generic about authoritarianism that makes it deteriorate over time. The model that follows is an exercise in atonement through model building.

The paper presents a theoretical structure inspired by the above reality. What the paper shows is that a modicum of dynamic inconsistency or present bias, which is a widely noted trait in human beings (Phelps and Pollak, 1968; O’Donoghue and Rabin, 1999; Kleinberg and Oren, 2014; Chakraborty, 2021), gives us this result.

As one ponders about this, it becomes clear that this is not just a theoretical possibility but, being based on realistic assumptions, it gives us insight into this troubling phenomenon, of strong leaders morphing into tyrants. Often big problems have simple root causes. What this paper shows is that the reason dictators morph into tyrants is, in terms of logic, the same as why George Akerlof procrastinated mailing Joseph Stiglitz’s parcel from India, after Stiglitz returned home and Akerlof stayed on for a while more (Akerlof, 1991). Every morning, [the thought of] the transactions cost of going to the post-office and standing in the queue that day acquired a salience in his mind, which made him decide he would mail it the next day. It was this series of present-biased decisions that led to the long procrastination.

The gist of the argument in the context of political leaders is the following. Consider a person who comes to power by overthrowing a bad leader, as Daniel Ortega did by overthrowing Anastasio Somoza Debayle. The new leader, even while helping the country to do better, will soon face the decision of whether to seek more time in office. Politics is a tough game, where you often have to indulge in evil acts in order to escape the fate of being evicted from power. So the person has to decide how far to go in terms of political intrigue and ruthless acts in order to stay in power. A common feature in making this optimization decision is dynamic inconsistency.

If the leader indulges in a certain amount of evil in order to remain in power and does thereby manage to stay in power, then during the next term or further in the future there may be an additional reason to want to stay in power. The evil acts of the earlier terms in office could mean that exit from office will be more costly. You will face inquiries about your acts while in office and may be punished [see footnote 1]. This will prompt greater evil acts to stay on in office, and that will make the exit option even worse, and the inexorable logic of this continues. Gaddafi must have realized, midway through, that voluntary exit was no longer an option for him. If he had done the full dynamic optimization at the start he may never have gone down this route.

What makes the ongoing Ukraine war so dangerous is that Putin is fast losing all exit options. We have enough evidence and analysis from behavioral economics to know that from procrastinators to drug addicts many fall into this trap. What the present paper argues is so may dictators and the final outcome can be bad for all.

Conversely, leaders who have got out of power have on occasions paid a heavy price for it. Cooter & Schäfer (2012) refer to this as the ‘dictator’s dilemma.’ A good illustration of this comes from Chile’s General Augusto Pinochet. He came to power after a brutal military coup in 1973, with non-negligible help from the CIA, against the democratically-elected leader Salvador Allende. He quickly morphed into a dictator, and ruled the country with an iron hand over more than a decade, killing thousands of opponent and torturing hundreds and thousands of his opponents, mainly leftists and socialists, during his term as leader of the nation. In 1990 he got out of power by offering his resignation. However, it was not a good life after exiting from power. He was soon charged with human rights violation, murder and torture during his term as president and was arrested in 2004. Citing the case of Augusto Pinochet, Cooter and Schäfer (2012, p. 219) point out, ‘This story depicts a dilemma: an aging dictator wants to resign from power, but he fears prosecution for crimes. His only effective guarantee against prosecution is to retain the power that he wants to relinquish.’

Dictator morphing: a model

To capture this dilemma simply, let us assume that the political calendar is broken up into terms, say four years for each term. Once in office, you are there for one term. During that term, you do many things as leader but you also have to decide whether to fight to stay on for another term. Consider the problem in the first term. It is a new leader and he has to decide his strategy. Suppose the amount of evil you indulge in is an element of [0, 1], where 0 means no evil and 1 is maximum possible evil. If you find it difficult to imagine what 1 means, look around the world. You will not have to imagine; you will find empirical examples.

The leader has to choose e ∈ [0, 1], where e represents the extent of evil they indulge in in order to stay in power. Suppose for simplicity that the probability of staying in power for another term is equal to the chosen e. The more evil you do the more likely you are to stay in power. Also assume, once one exits office, one does not return again. This simplifies the analysis.

Let the joy or payoff of being in power for one term be denoted by x and the payoff of being out of power be y. Assume x > y. [see footnote 2]

Few like to do evil. Let the guilt and remorse of doing evil, e, be given by r(e), where r'(e) > 0, all e.[see footnote 3] Finally, I assume r'(e) > 0 and r(1) > x and r′(0) < x-y.

Condition 1 is made simply to ensure that there is an interior solution. I will work with y > 0 but this is not necessary.

It seems likely the politician, trying to decide whether to stay on in office for another term, will do the following optimization.

He will try to choose e to maximize: π ≡ xe + y (1 − e) − r(e). (2)

Hence, e is derived from the first-order condition of maximizing π: (x − y) = r′(e).

Figure 1 illustrates this maximization exercise, with the equilibrium choice of evil, e∗.

The line yP depicts xe + y(1 – e); and the r(e) graph is also shown in the figure. The politician wants to maximize the gap between the two, described by (2). This happens at e∗.

Note that (1) implies that e∗ > 0. Hence, this level of evil causes remorse given by r(e∗), which is greater than 0 and is shown in the picture by Be∗. However, it has a net benefit of AB. AB is the largest gap between the line yP and curve r(e). Hence, AB is greater than y, shown in the figure by the line segment y0. This means that indulging in no evil, that is e = 0, lowers the cost of remorse to 0, but you lose power for sure after one term and that is not attractive.

There is, however, a ‘mistake’ the leader makes here, which is common and natural. That is the mistake of not being far-sighted enough.

Typically, if you indulge in evil and stay in power, your cost of exit in the next period will rise. That is, in the next period, the payoff from exiting from power (that is, the y of the next period) will be lower. There will be inquiries about why you, as president or prime minister, indulged in unlawful, evil acts? There may be cases brought against you; and you may even be incarcerated. This has happened to leaders in history. The fear of this must stalk Bolsonaro, Erdogan, Lukashenko, Orban, Ortega and Putin – presented, I hasten to add, in alphabetical order.

To understand this, note that the above analysis was done assuming that life (in politics) consists of two (potential) terms, which means there is only one decision point which is the first term. This is because there is no decision to be taken in the final term, since in this model the only decision concerns how much effort you are willing to spend for one more term in office. In life’s last term, that decision does not arise. To put it another way, in the last term, you will mechanically choose e = 0.

Now think of the problem more generally as consisting of T-terms, where T > 1. The leader has to take a decision in T-1 terms, that is, in all but the last term. The dynamically inconsistent person, which is the way most human beings are, treats each decision, without detailed calculation of the full future. If the leader thought of the full life’s decisions as one big optimization problem, the calculation would be different. At each period, she would have to recognize the next period’s payoff from exiting from office is a decreasing function of the level of e chosen in this period. If in period t, the leader chooses evil et and the payoff from leaving power in the next period is yt + 1, what I am asserting is that [see footnote 4]:

y t+1 = f (e t) , f ′ (e t) < 0.

If we denote the net payoff in each period, t, by πt, which is defined the same way as (1), above, then the full optimization exercise consists of choosing (e1 , e2 , . . . e T−1) to maximize

π1 + π2 + · · · + πT−1 .

The main theorem is the following: There exist parameters, under which, if this full optimization is done, the political leader will choose e t = 0, for all t.

However, if the choice is made in each period, unmindful of the fact that this term’s choice of e, will have an effect on next term’s value of y, or treating this term and the next term as the only two terms of life, then the politician will choose (e1 , e2 , . . . e T−1) such that e1 < e2 < · · · < e T−1.. That is, the extent of evil actions chosen will increase monotonically with each term in office.

The process of morphing into a tyrant is inexorable. The consequence of the cost of exit getting higher in each term is that you will have to indulge in even greater political intrigue, ruthlessness and evil to make sure you do not get thrown out of office. The following period you have to do even more. Ultimately, you morph into late stage Alexander Lukashenko, Vladimir Putin or Daniel Ortega.

If they knew how to do dynamic programming right, they may not have got into the process at the start, done one good term in office and left. But this kind of short-sightedness, whether we call it hyperbolic discounting or just unawareness of the full impact of your action into the future, is a common human mistake. The problem is that this has devastating consequences for the well-being of society and the world, as we can see from the Ukraine war.

One can give a formal proof of the theorem for the T-period game by solving the full optimization. But the intuition is easy enough that the algebra is redundant. I give a proof here for the case where T = 3; so that there are two decision points. The entire proof is obvious using one diagram, Figure 2.

A part of Fig. 2 is a reproduction of Fig. 1, where the leader chose e∗ in period 1, when the exit option was y, where y = f(0), since at the start there is no history of evil. Denote f(e∗) by y’. We know that y’ < y, since f’ < 0. It is easy to see that as y falls, the line yP becomes steeper by pivoting around point P. This is because, as one can see from (1), at e = 1, π is independent of y. Hence, as y falls to y’, the earlier line, yP, pivots at P and become y’P.

If we now denote the optimal choice of e by e’, it must be that e’ > e∗, since r'(e) > 0.

Now it is entirely possible to think of parameters such that, the leader, if she did the full optimization for the three-term game, she would prefer to choose e = 0 in both decision points (that is, in terms 1 and 2), rather than choosing e∗ and e’ as he does when he is short-sighted and ignores the effect on his exit option when he chooses 2.

To see this, note that, if she chooses e = 0 in both the first term and the second term, the total benefit he gets over time is x + y + y. This is because, in term 1, she is in office and so gets x. Since she chooses e = 0, in term1, she incurs no remorse from choosing evil but she has to leave office and so gets y. Once out of office, always out of office; so in term 3 she again gets y.

Next suppose he chooses e∗ and e’ in term 1 and term 2. The total payoff she gets over time is x + AB + (1 – e∗) y + e∗CD, where the AB and CD refer to the line segments in Fig. 2. This is easy to see. In term 1, she is already in office and gets x. By choosing e∗ in term 2, she gets AB. But choosing e∗ means she has a probability (1-e∗) of losing power, in which case she gets y or probability e∗ of staying in power, in which case she gets an expected payoff of CD.

All we need to show is that it is possible that: x + y + y > x + AB+ (1 – e∗) y + e∗CD. In other words, we have to show: (1 + e∗)y > AB + e∗CD.

From the fact of the leader’s optimization, we know that in Fig. 2, AB is greater than both y and CD. But this is compatible with y being close to AB and CD being much smaller than y, which would make the above inequality valid. This completes the proof. It is intuitively obvious that, in the general case, with T > 2, even if a leader does the optimization for a few periods into the future at a time (instead of just one period at a time, as in the above example), but not the whole length of the future, she could end up on a path where she has to indulge in increasing evil acts to stay in power, morphing fully into a tyrant after some stretch of time in office.

Before commenting on the normative and policy implications of the above claim, I want to add a few technical comments and caveats.

First, note that some neoclassical economists assume people are always rational and so they reject some of the premises of behavioral economics. At times this becomes a tautology. They assume people are always rational and, no matter how they behave, they describe this as rational behavior. This leads to contortions of the model to ensure that dynamic inconsistency, which implies a form of intransitivity of preference, cannot occur, by definition. Interestingly, there is work in philosophy (see Parfit, 1984), that asserts how, especially in domains of moral decision-making, people may be fully rational and violate transitivity.

Taking cue from this, we can create models where dynamic inconsistency is compatible with rational behavior. That is, it is possible to conceive of contexts where there is a set of decisions to be taken over time, each decision is taken fully rationally, but at the end of it all, the individual has reason to regret the choices. This is possible in contexts where there is an infinite number of decision points [see footnote 5].

In the present context, if we assume that this is an infinite decision problem, that is, during a politician’s lifetime, there are an infinite number of occasions where she can decide what to do to enhance her political power, we can create a game akin to some of the art of M. C. Escher, where each step enhances the players utility, but the player ends up with a utility level, below where she had started. I argued elsewhere (Basu, 1994), this can happen not just in art, but in games.

Second, the above model showing the morphing of tyrants was presented using many strong assumptions. The reason is that my claim is not that the morphing will always happen, which would require proving it under the most general conditions, but that there is a propensity for this to happen under reasonable situations. However, it is worth pointing out that many of the assumptions can be relaxed without losing the result. For instance, the assumption that the function r(e) is increasing and convex can be generalized if we relax the assumption that the probability of winning another term is equal to e, as assumed in the above model. Allowing for non-linearity in this will allow us to relax some of the restrictions on r(e) and to get the same result.

Third, the fact that it was assumed that it is political intrigue and evil, variable e in the model, that helps authoritarian leaders to prolong their hold on power, may suggest that it is being assumed that doing good does not help retain power. That is not however an assumption being made here. In fact, doing good, or at least doing visible good, will typically help prolong a leader’s term in office. However, that is a tactic that all leaders will use because doing good will make them feel good and help society.

Hence, this is a strategy that will be used by all. The interesting challenge arises when this strategy is exhausted and the leader has to choose e, and hence that is what the model focusses on.

Finally, there is one important assumption used in the paper that may be worth trying to generalise in the future. Note that in the above model it is assumed that the leader chooses e, keeping in mind that the payoff of failing to remain in office is given by y. In reality, the y will itself depend on the e, and as e increases, y will fall, that is, the exit option for the dictator will get worse.

Leaders with a little far-sightedness, even if they are not doing the full optimization over time, should be aware of this. This injection of reality will complicate the model. However, if we assume that y depends on the accumulated evil indulged by the leader in the previous terms in office, plus the evil done now, that is, e, to stay in office for another term, it should be possible to build a more sophisticated model which will continue to give a result similar to the one obtained in the present paper.

Some normative questions

This paper is part of a larger discourse on the power of the leader or the state, and the risk of oppression and violation of basic human rights of individuals that goes back to the 17th century, but has been a topic of contemporary interest, as part of a larger discourse on collective action and power (Hobbes, 1651; Acemoglu and Robinson, 2019; Binmore, 2020; Ferguson, 2020; Lopez-Calva and Bolch, 2022; Basu, 2022b). It is possible to argue that leadership is often needed to achieve the social good, but there is always the risk of the leader going astray, or morphing into a force of evil, as the above model illustrates. Given this very real problem of political economy, what can we do by way of policy and prior regulation to prevent such a predicament? How do we put checks and balances on the leader?

Most problems of political economy are unlikely to be fully solvable. This is because, in reality, there is no such thing as the ultimate game of life. As you devise rules to prevent people or players from indulging in bad behavior, they can keep finding new strategies, beyond the original game of life [see footnote 6], to perpetrate evil. The only hope for well-meaning policymakers is to try to stay ahead of the curve. It is in this spirit that I offer some closing comments, aware that they raise more questions than answers.

At this time, what the above theoretical model points to is the need for ex ante agreements, akin to constitutions, which debar certain kinds of actions by human beings. The key is to have agreements in advance which deter certain behaviors in the future.

Why would such agreements work? One reason, rooted in economics and game theory but not widely understood, is that the social, political and economic world we inhabit has multiple equilibria. Prior agreements are ways of nudging ourselves away from the current equilibrium to another collectively more desirable equilibrium. The key word here is ‘equilibrium’. If this is done successfully, the question of why people will adhere to a constitution is easy to answer. If the constitution is a set of rules which has the property of constituting an equilibrium, then once it becomes focal it will be adhered to simply because it is in each person’s self-interest to abide by the constitution if others abide by the constitution. I am using the term ‘equilibrium’ in a somewhat unconventional way, to denote a stable vector of sets of omitted strategies. Each player agrees not to use certain strategies if other players agree not to use some of their strategies [see footnote 7].

By this criterion the challenge is to draft a constitution that happens to be one of the equilibria of this society and then create pressures so that this equilibrium becomes a focal point to which people are willing to shift. Further, in our globalizing world the need is for a global constitution and global agreements. Globalization raises important questions of global justice (Hassoun, 2012). Just as we have an obligation toward the global poor, we have an obligation toward those whose basic human rights are violated by dictators and tyrants, no matter where they live. We are at a stage of history, where we have no escape but to be more intrusive in other nations. There will have to be lines, which, if nations cross them, others acquire the right to intervene.

While striving for such agreements and constitutions, it is worth keeping in mind that there are other options, which require us to step beyond the conventional idea of equilibrium. The belief that individuals choose from the universal set of all available actions, and they choose rationally from this set, as mainstream economics assumes, is deeply flawed. First of all, we all have social norms and moral hard-wirings that we adhere to. What is ignored in mainstream neoclassical economics is that these moral and normative moorings are often critical for markets to function and society to prosper (Basu, 2000, Chapter 4; Bowles and Gintis, 1998; Bowles, 2016). Further, these norms may change and get modified over time, solving and occasionally creating new problems. These norms are often so embedded in our psyche that we abide by them unwittingly. We do not bite others, even when that would clearly help us, not because this action is not available in the game of life, nor because on doing cost-benefit analysis, we find this does not give us a positive payoff, but simply because our norms have programmed us not to even consider this action.

There are other ways in which the notion (common in economics) of human beings having exogenously given preferences or payoff functions, has been contested. We know, for instance, that people often choose actions in order to enhance their self-esteem (see Crocker and Wolfe, 2001; R. Akerlof, 2017b). Moreover, there is often a tussle between self-esteem and the esteem of peers. If being in power raises esteem (of oneself or of the peers), a political leader may try harder to stay in power. If, on the other hand, giving up power, when one could have clung on to it, raises esteem, the leader may be more inclined to quit office.

The awareness of these norms and endogenous elements in human preferences opens up a vast terrain of research and analysis that goes beyond mainstream economics and straddles the terrain between sociology and economics (Kliemt, 2020; Coyle, 2021; Basu, 2022a). This can also bring to light new avenues for modifying our behavior in order to create a better world. By changing what we esteem in our peers, we can prompt our peers to behave differently. This is a matter of some urgency in our troubled world. Though the definitive answer to this may take time to evolve, it is a direction of research worth pursuing in the future.

Let me close by addressing a narrower matter, which arises directly from the above model. This concerns having global rules concerning term limit. A tyrannical leader in one nation can destabilize the world. So, ideally, we need a term-limit requirement built into an international charter or a global constitution. If the T, in the above game, is capped by a charter at 2, there will be only that much evil a leader can morph into. What is more important, is that leaders, being aware that they will have to exit, will be more conscious of their behavior when in office [see footnote 8].

It is possible to think of more immediate actions, that is, even before a global agreement is reached. For this, we have to get away from our propensity to think of nations as individuals or players. Thus the Cuban missile crisis is typically modeled as a two-player game, USA and USSR locked in a deadly Hawk-Dove scenario. Likewise, there is a body of writing on the war games in the Korean Peninsula and what we can do to avert disaster. This is conducted mostly in terms of a game between North Korea, USA, China and Russia, occasionally tossing in South Korea. Much of this is done again treating nations as players. When individuals are brought in, like Kim Jong-un, they are treated as having interests totally aligned with their own nation – ‘Kim Jong-un is an ardent nationalist who regularly responds to threats by upping the ante’ (Menon, 2017).

What is not always recognized in popular discourse but is a central tenet of modern political economy, at least since the seminal work of Downs (1957), is that leaders have their own interests, which are not aligned with the interest of the nation. Many dictators who have long been in power may want to exit purely for their own interest, but they may not have a viable exit option [see footnote 9]. They know that, once out of power, they will be punished by their own people or even killed by the generals.

It is not immediately clear how to solve this. Some may argue that the way to solve this is to create attractive exit options. This would amount to the US telling Kim Jong-un, ‘If you stop oppressing your people and threatening other nations, we will protect you by helping you leave your country, and give you a castle on a pacific island to settle in.’ This could help us deal with Kim Jong-un and promote peace in his nation and the world. But no problem in economics comes with the absolute final answer. If the US uses this strategy regularly for world peace, we will have another problem. Individuals with no interest in power and tyranny may now strive to become tyrants for no other reason but to get that castle in the Pacific Island.

Acknowledgment

The paper began with a presentation at the Fifth Conference of Philosophy, Politics & Economics (PPE) Society, New Orleans, 3-5 February 2022, and was developed further as part of my W. Edmond Clark Distinguished Lecture at Queen’s University, Canada, delivered on 6 April 2022. The nudge to bring the paper to closure needed the free-flowing conversation I had with Hartmut Kliemt. En route to completing the paper, I had conversations with and received comments from many. I owe special thanks to George Akerlof, Nancy Chau, Chris Cotton, Joe Halpern, Nicole Hassoun, Chenyang Li, Hans-Bernd Schäfer, Arunava Sen and Saloni Vadeyar. I want to thank the Bucerius Law School, Hamburg, for hosting me during the last lap of work and Cornell University’s Microeconomic Theory workshop where I presented the paper. Finally, I would like to thank two anonymous referees of the journal for valuable comments, many of which are now part of the text.

Footnotes

1. It is also possible that as people indulge in such acts they internalize these as not evil acts but hard decisions one has to make for the good of the nation. Such delusions make it easier to live with oneself. Their persistence is also made more likely by the advisers who surround the leader and misinform and help create such a make belief world. For simplicity of analysis, I shall stay away from these complexities.

2. The constituents of the joy of being in office are not modeled here. One joy could come from being able to do what you believe is good for the nation. The reason why you may be able to do good in office is that being in office is a way to get legitimacy over others. You can simply give orders to incentivize others (Akerlof, 2017a). This is what leaders do and it is not hard to model this (Basu, 2022b).

3. It is possible that some of the power-hungry leaders, feel no remorse or guilt. That will simply reinforce the result. What makes the result obtained in this paper more interesting is that it survives even if the leader does have guilt-feeling.

4 The assumption that the cost of evil acts upon exit from office happens in the next period is made for algebraic simplicity. It is arguable if one acts evil and fails to remain in power one will have to pay for the evil right away. This will yield the same result as in the paper if we make the payoff upon exit to depend on the accumulation of all past terms in office including the immediate one. In other words, we could assume, y t = f (e1 + e2 + . . . e t) , where f ′ < 0. We would end up with a little more algebra and the same result.

5. There is a literature that shows how this can happen and, more generally, discusses the case of infinite decision points, with one player making an infinite number of decisions or a countably infinite set of players, each making one or a finite number of decisions (Voorneveld, 2010; Cingiz et al., 2016; Rachmilevitch, 2020).

6. Thereby raising troubling questions about the very meaning of ‘the game of life’ (Basu, 2022a).

7. The idea of an equilibrium of omitted strategies (instead of a vector of selected strategies as in conventional game theory) leads to various concepts of set-valued equilibria in games (see Basu and Weibull, 1991; Arad and Rubinstein, 2019). These set-valued notions are germane to understanding the meaning of a constitution in a formal way.

8. All real-life solutions come with caveats. It must be recognized that term limits have some disadvantages. It makes politicians focus on the short duration at the expense of long-term gains for society. On the other side, having term limits can encourage dynasties, which act as a substitute for one leader carrying on for too long. The reign of Kim Il-sung, Kim Jong-il and Kim Jong-un, from 1953 to now, is, for all practical purpose, rule by one person.

It is worth emphasizing here that ‘interest’ has come to acquire a rather unidimensional notion of economic interest and this has had wide influence in the way we do our analysis and formulate policy. In contexts such as the one analyzed in this paper, we have to remind ourselves that ‘interest’ is a complicated multi-dimensional idea (Swedberg, 2005). This may make policymaking harder, but it can make policymaking more effective.

This paper was originally published in Oxford Open Economics.