Why ‘historic’ pact may not give Tripura’s tribal communities a new deal

The Tipra Motha, led by erstwhile royal Pradyot Kishore Manikya Debmarma, has long advocated for the cause of Greater Tipraland, an independent state for the tribal communities of Tripura.

Days after signing the pact, the Motha, which is also the largest Opposition party in the state, joined the coalition government in the state led by the Bharatiya Janata Party.

While the pact is being seen as handing the Bharatiya Janata Party an advantage ahead of the Lok Sabha elections, observers remained sceptical about how effective the agreement will be in securing the rights of the tribal community, which since Independence has become a minority in Tripura.

The one-page pact signed by the three parties is silent about the demand for Greater Tipraland.

The pact

On March 2, the Centre, the Tripura government and the Tripura Indigenous Progressive Regional Alliance or the Tipra Motha “agreed to amicably resolve all issues of indigenous people of Tripura” relating to history, land and political rights, economic development, identity, history, culture and language.

The one-page statement issued by the Union home ministry said that the three sides “agreed to constitute a joint working group/committee” to work out and implement “mutually agreed points in a time-bound manner to ensure an honourable solution.”

Union home minister Amit Shah said it was a “historic day” for Tripura. “With this agreement, we have honoured history, rectified mistakes and by accepting the present reality we have taken a step for the future,” Shah said after the signing of the pact in Delhi. “No one can change history but we can learn from past mistakes and move ahead.”

The idea of a Greater Tipraland envisages an area that includes the area currently under the Tripura Tribal Areas District Autonomous Council, or TTADC, as well as places inhabited by the Tiprasa tribe outside the council areas. Among the demands of the Motha is greater autonomy for the council in matters of land rights and finances.

In recent years, the Motha has outstripped the other tribal party in the state, the Indigenous People’s Front of Tripura or IPFT, in popularity. The IPFT, too, had espoused the cause of a separate tribal state.

But it was Tipra Motha that earned a decisive victory in the district council elections in 2021 – two years after it was formed – and emerged as the second largest party in the Assembly polls last year.

With its growing influence and popularity, the Centre and Motha started negotiations right after the new government was formed last year.

A troubled history

The demand for a separate state stems from deep-rooted anxieties about the dominance of Bengalis in Tripura, many of whom migrated to the state from East Pakistan after Partition and, later, during the 1971 Indo-Pakistan war.

The wave of refugees led to a sharp change in demography in the state – in 1948, the indigenous tribes accounted for over 80% of the population, now they are around 30%.

Between the 1970s and the 1990s, the state saw the rise of several tribal insurgency outfits demanding a separate homeland for the Tiprasa tribe. Though the 1988 accord between the Tripura National Volunteers and the Indian government ensured a fragile peace, the demand for a separate homeland never went away.

Since its inception in 2019, Tipra Motha has demanded a separate state for the state’s over 11.66 lakh tribal population – about 31% of the state’s population, who live in 70% of the state’s land area.

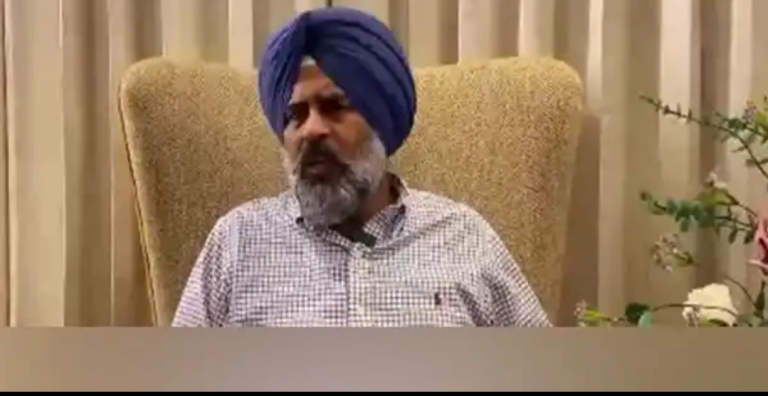

For the first time, the government of India has acknowledged there were “historical mistakes” against the indigenous people, Pradyot Debbarma told Scroll. He counted it as a significant victory and claimed that 60% of the group’s goals have been met.

Do tribal residents gain?

The signing of the pact has been met with a fair degree of scepticism in Tripura. Much of this is due to the sketchy details surrounding the agreement – which was announced by the one-page statement issued by the Union home ministry.

That statement, observers point out, is silent on the demand for a Greater Tipraland or greater autonomy over land to tribal councils.

“I don’t know how they [Motha] are going to explain this pact to the tribal people, to their supporters,” said Bikash Rai Debbarma, writer and president of Kokborok Sahitya Sabha, an influential cultural organisation of the tribal community. “The stone is yet to roll. How are they saying that 60% is already done?”

However, Pradyot Debbarma told Scroll that the one-page agreement is only the “preamble of the framework”.

“It is not the agreement document,” he said. “Everything inside the framework needs to be discussed within a timeframe of six to eight months.”

Bikash Rai Debbarma pointed out that Tripura’s tribal residents have walked down this path before.

In 2018, the Centre had formed an inter-departmental high-powered modality committee to study socio-economic, political, cultural and linguistic problems of tribal communities in Tripura following an agitation by the IPFT, which is now the BJP’s alliance partner.

“The outcome of that committee is almost zero,” Debbarma said. “This time the committee has not yet been formed, the time frame is not given and what will be the terms of references that also is not clearly stated,” the veteran Kokborok writer said.

An elected BJP member from a tribal community told Scroll that it is not clear what the tribal communities are getting from the agreement.

“We do know if the agreement will increase the reserved seats from 20 Assembly seats to 25 or 26 for the tribals,” the BJP elected representative said. “We want the Kokborok language to be included in the Eight Schedule. In tribal areas, we have been demanding the establishment of a three-tier panchayat system, and direct funding from the Centre to the Tripura Tribal Areas Autonomous District Council. The pact does not talk about any of this.”

He added: “Let’s see what changes in six months.”

A signatory of the agreement told Scroll that the pact includes 12-14 pages, which have not yet been made public and which list the issues to be discussed by the joint working group.

“The power to allot land does not lie with the district council in Tripura, but the deputy commissioner – unlike how it is in Meghalaya or Assam’s Karbi Anglong or Bodoland,” the signatory said. “The agreement will enable the council to grant land to the tribals.”

Advantage BJP

Ahead of the Lok Sabha elections, the agreement gives the BJP an advantage.

The alliance with the Motha implies it no longer has to worry about the tribal vote going to the Left and Congress parties.

During last year’s state Assembly election, in several constituencies reserved for Scheduled Tribes, the BJP had won because of a split in Opposition votes.

Tripura accounts for two Lok Sabha seats, including one reserved, but both are Bengali-majority seats. Since 2017, a large chunk of the Bengali votes has moved to the BJP from the Left and the Congress.

“The crucial tribal voters stay with Pradyot and it helps to counter any coming together of the Left and Congress in Tripura,” said RK Debbarma, who teaches political science at the Tata Institute of Social Science in Guwahati.

The tie-up between the BJP and the Motha might also help the saffron party blunt any resentment in the state over the Citizenship Amendment Act, the rules for which were notified on Monday.

For example, a clause in the agreement bars all parties from public protests.

“In order to maintain a conducive atmosphere for implementation of the pact, all stakeholders shall refrain from resorting to any form of protest/agitation, starting from the day of signing of the agreement,” the agreement said.

Agartala-based author and journalist Manas Paul said this assurance to the government from Tipra Motha preempts any protests by the tribal group against the Citizenship Amendment Act.

Pradyot Kishore Manikya Debbarma is among the petitioners who have challenged CAA in the Supreme Court. In the last Assembly election, the Motha had promised to pass an Assembly resolution against the contentious law if it was voted to power. Tripura had witnessed large-scale protests in December 2019 after Parliament passed the bill.

High stakes for Tipra Motha

Having taken on the baton of tribal subnationalism from the IPFT, Pradyot Debbarma was under pressure to deliver. Said Manas Paul, the journalist: “He stirred the emotions of the indigenous people so fiercely that he is riding a tiger. He cannot get down from it now.”

The pact, said Paul, might be his way of finding a “dignified retreat.”

Many observers see in the agreement a backtracking from the demand of a separate state, though Pradyot Debbarma told Scroll that “nowhere is it written in the pact that he has given up on the demand”.

Political scientist RK Debbarma said the agreement signals the limit of “identity politics” which plays on the “emotions” of the tribal people. The most pragmatic outcome, he said, could be more autonomy under the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution. “Beyond that, there is nothing that the Constitution can offer.”

The tribal areas of Tripura enjoy protections and safeguards under the Sixth Schedule, a constitutional provision that provides for decentralised self-governance in certain tribal areas of Assam, Meghalaya, Mizoram and Tripura.

Debbarma added: “Tripura cannot be like Mizoram or Bodoland, where only one ethnic group is dominant. A state based on one ethnic group is a recipe for disaster.”

But given the resonance of the demand for a separate state, the Motha might find itself upstaged by another tribal group in the future if it fails to deliver on its promises – just as it had upstaged an older group. “The IPFT also promised a separate state, got the Centre to form a committee and then within two years they lost their vote bank to Pradyot,” said RK Debbarma.